Kevin Riford

You might be wondering how Jeffrey Epstein and those who conspired with him were able to operate for so long without meaningful consequences. Over the years, numerous victims came forward — with reports dating back as early as the 1990s — yet little action was taken. How could so many allegations be raised and seemingly pushed aside?

Today, we’ll examine documented examples of how that protection and inaction occurred.

1.) The Media

In 2019, a “hot-mic” video was released after being leaked by the activist group Project Veritas, capturing ABC News anchor Amy Robach speaking off-camera about a Jeffrey Epstein story she had worked on years earlier. In the recording, Robach said that in 2015 she secured an interview with Epstein accuser Virginia Giuffre (then known as Virginia Roberts), but the network never aired it. She expressed clear frustration, saying she had possessed material for three years that she described as “unreal,” yet the story “would not get on the air,” despite her belief that it was highly newsworthy.

In the clip, Robach claimed that ABC leadership had dismissed Epstein at the time, allegedly calling it “a stupid story” and not worth pursuing. She also suggested there were concerns within the network about potential repercussions involving powerful individuals named in the interview. According to her remarks in the video, she felt strongly that the reporting should have been broadcast and implied that internal decisions prevented it from moving forward.

2.) Intelligence Agencies

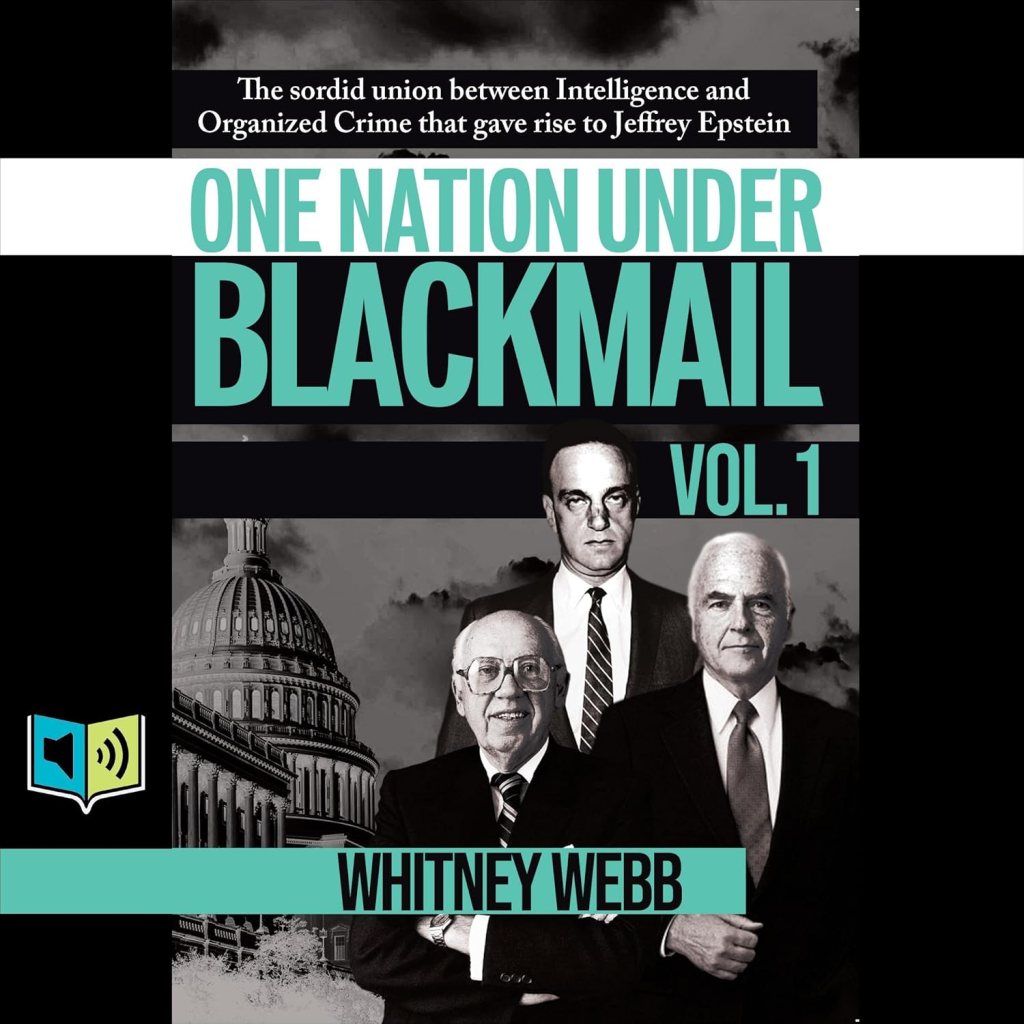

In One Nation Under Blackmail, Whitney Webb also explores the relationship between intelligence agencies and major media institutions. She argues that throughout the 20th century — particularly during the Cold War — intelligence services cultivated relationships with journalists and media executives to shape public narratives. Historically documented programs, such as the CIA’s alleged efforts to influence journalists during that era, are cited as examples of how information channels could be leveraged to promote certain stories while downplaying or discrediting others. In Webb’s view, these relationships did not always require direct control; sometimes influence operated through access, career incentives, or shared institutional interests.

Applied to the Epstein case, Webb suggests that media inaction or delayed reporting may reflect this broader dynamic. She argues that powerful individuals connected to intelligence, finance, and politics often overlap socially and professionally with major media leadership. Within that ecosystem, she contends, certain stories can face higher internal barriers — especially when they implicate elite networks. Rather than overt censorship, she describes a system where editorial caution, legal risk concerns, and institutional self-protection can collectively result in sensitive allegations being sidelined.

Webb’s perspective portrays media not simply as passive observers but as participants within a larger power structure. While she does not claim every newsroom operates under intelligence direction, she suggests that longstanding relationships between national security institutions and major outlets create environments where narratives can be managed. This interpretation remains debated, and many journalists reject the idea of systemic coordination. Still, in her broader thesis, the intersection of intelligence, organized crime, finance, and media forms part of the explanation for how figures like Epstein were able to avoid sustained public scrutiny for years.

Webb points to World War II and early Cold War operations, arguing that U.S. intelligence (particularly the CIA’s predecessors) cooperated with Mafia figures for operational purposes.

She often references:

- Alleged U.S. Naval Intelligence cooperation with mob figures in New York during WWII (sometimes called “Operation Underworld”).

- Post-war anti-communist operations in Europe, where former criminal or extremist networks were allegedly used for intelligence objectives.

Her broader claim: intelligence agencies learned that criminal organizations were useful because they already operated in secrecy, controlled illicit supply chains, and were accustomed to violence and coercion.

Webb argues intelligence agencies sometimes:

- Used criminal groups for arms trafficking, drug trafficking, and covert funding

- Relied on organized crime figures for deniable operations

- Leveraged criminal networks for political influence or destabilization efforts abroad

The key concept in her book is plausible deniability — governments could distance themselves from illegal acts by routing operations through criminal intermediaries.

A central theme of her book is the use of sexual blackmail and kompromat (compromising material).

Webb suggests:

- Intelligence agencies historically used sexual entrapment operations.

- Organized crime figures were sometimes involved in facilitating such operations.

- Jeffrey Epstein’s activities fit into what she portrays as a longstanding model of gathering compromising material on powerful individuals.

3.) “Private Investigators”

According to reporting by The New York Times, Epstein hired Black Cube operatives to allegedly:

- Approach journalists who were investigating Epstein.

- Attempt to gather information about accusers.

- Used false identities in some interactions.

- Tried to undermine or discredit claims being made against him.

There were also reports that Epstein hired private investigators to surveil and gather information on potential witnesses, including women who had accused him of abuse.

Hiring private intelligence firms is not illegal in itself. However, the tactics described — particularly impersonation and efforts to intimidate or discredit accusers — reflected a broader strategy to protect Epstein’s reputation and limit legal exposure.

This pattern fits with what many observers describe as Epstein’s long-standing approach: using wealth, legal teams, and private operatives to shield himself from scrutiny.

4. U.S. Attorney Alex Acosta

In 2019, The Daily Beast reported that during a transition interview for a position in the Trump administration, Acosta allegedly said he had been told that Epstein “belonged to intelligence” and to “leave it alone” during the earlier federal investigation.

This report surfaced after Epstein’s 2019 arrest reignited scrutiny of the 2008 non-prosecution agreement, which allowed Epstein to plead guilty to state charges and avoid federal prosecution despite extensive evidence gathered by investigators.

Donate

Donate